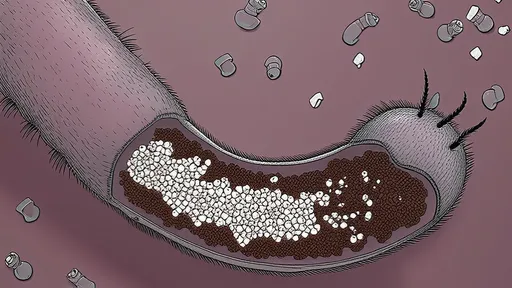

In a groundbreaking development that could revolutionize organ transplantation and autoimmune therapies, scientists have unveiled a novel approach to achieving "acoustic invisibility" for specific tissues. By harnessing precisely tuned ultrasound waves, researchers have successfully shielded transplanted pancreatic islet cells from immune detection in animal models. This technique, which creates a temporary protective bubble around delicate cells, offers hope for millions suffering from type 1 diabetes who currently face lifelong immunosuppression after islet cell transplants.

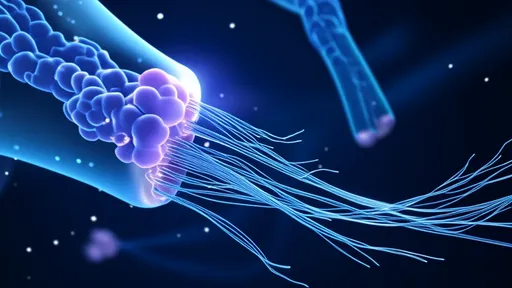

The concept builds upon emerging work in acoustic metamaterials - artificially engineered structures that manipulate sound waves in unconventional ways. While most applications have focused on sonar evasion or architectural acoustics, medical researchers recognized the potential to adapt these principles for biological camouflage. "We're essentially creating an invisible cloak made of sound," explains Dr. Elena Vasquez, lead researcher at the Institute for Biomedical Acoustics in Zurich. "The ultrasound field subtly alters how immune cells perceive the protected tissue, making it disappear from their surveillance radar."

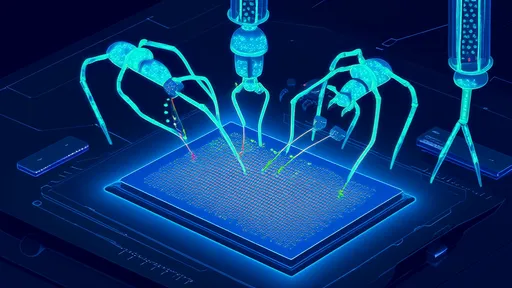

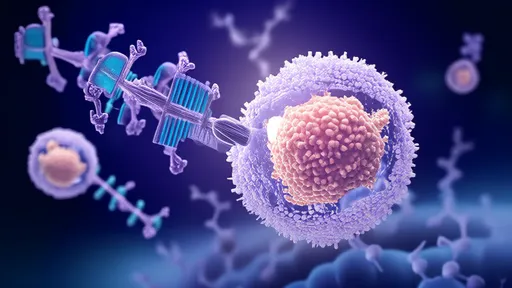

Early experiments demonstrate remarkable precision in the technique's ability to hide transplanted islet cells while leaving surrounding tissues unaffected. Unlike pharmaceutical immunosuppression that blankets the entire body, this localized approach could dramatically reduce infection risks and other complications. The ultrasound array, about the size of a wristwatch, creates interference patterns that disrupt the chemical signals immune cells use to detect foreign tissue. Preliminary results show protected islet cells surviving three times longer than unprotected transplants in primate studies.

What makes this discovery particularly exciting is its potential reversibility. Current immunosuppression drugs create system-wide effects that linger for weeks after stopping treatment. The acoustic shielding, however, can be instantly adjusted or turned off as needed. "This gives physicians unprecedented control," notes transplant surgeon Dr. Raj Patel of Massachusetts General Hospital, who was not involved in the research. "We could theoretically activate protection during high-risk rejection periods and deactivate it to allow immune surveillance when appropriate."

The technology's development faced significant hurdles in achieving the perfect frequency balance. Ultrasound too intense would damage cells, while insufficient energy would fail to create the masking effect. After two years of animal testing, the team identified a sweet spot between 800 kHz and 1.2 MHz that provides robust protection without tissue heating or other adverse effects. The current prototype maintains this protective field for up to eight hours per charge, with work underway to extend this duration.

Beyond diabetes treatment, researchers speculate about applications in other autoimmune conditions and organ transplantation. Rheumatoid arthritis patients might one day receive protected joint injections that avoid immune attack. The approach could potentially shield entire organs during transplant procedures, buying critical time for the body to adjust to new tissues. However, significant challenges remain before human trials can begin, including miniaturizing the technology for implantation and ensuring long-term safety.

Ethical considerations are also coming into focus as the technology advances. Bioethicists caution about potential misuse in military applications or the creation of "privileged" biological tissues that permanently evade immune detection. The research team has established strict protocols to prevent unauthorized applications while collaborating with regulatory agencies to develop appropriate guidelines. "Like any powerful medical innovation, this requires careful stewardship," emphasizes Dr. Vasquez. "Our goal isn't to trick the immune system permanently, but to create temporary safe zones for healing."

Investors have taken notice, with venture capital firms pouring $47 million into the startup commercializing the technology. The company plans to initiate FDA discussions later this year, targeting conditional approval for compassionate use in terminal diabetes cases by 2026. Meanwhile, academic labs worldwide are racing to explore variations of the technique, including combining acoustic shielding with stem cell therapies for enhanced effects.

As the field of immunoacoustics emerges, it's becoming clear that sound waves may join pharmaceuticals and biologics as a third pillar of immune modulation. The implications extend beyond medicine into basic science, offering new tools to study immune cell behavior in real time. Researchers are particularly excited about using the technology to observe how immune systems gradually accept foreign tissues when introduced in controlled, protected environments.

While much work remains, the successful animal trials mark a turning point in how scientists approach immune system management. The era of brute-force immunosuppression may be giving way to more elegant, targeted approaches that work with the body's natural defenses rather than overwhelming them. For patients awaiting transplants or suffering autoimmune destruction of their own tissues, acoustic invisibility offers hope for treatments that are both more effective and less disruptive to normal immune function.

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025