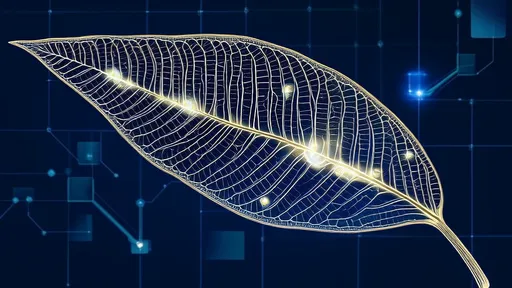

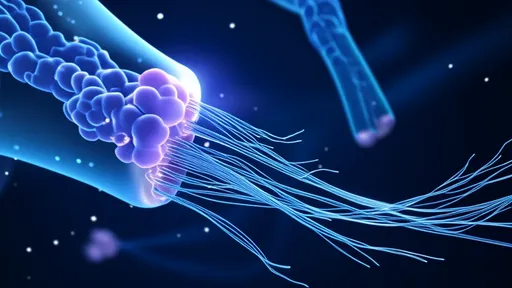

The hidden economy of the forest floor operates on a currency more ancient than human trade systems: carbon. Beneath our feet, vast mycorrhizal networks act as subterranean stock exchanges, where trees and fungi negotiate complex deals of nutrients for carbohydrates. Recent research reveals these symbiotic relationships involve sophisticated dynamic regulation of carbon allocation - a natural "carbon coin" system that maintains forest health and resilience.

For decades, scientists understood mycorrhizae as simple reciprocal exchanges - fungi providing minerals to trees in return for sugars. But advanced isotopic tracing techniques have uncovered a far more nuanced economy. Trees don't uniformly distribute their photosynthetic earnings; they strategically allocate carbon to fungal partners based on seasonal demands, environmental stresses, and even the competitive landscape of the surrounding forest. This dynamic redistribution challenges our basic assumptions about plant behavior and intelligence.

The Carbon Marketplace Beneath Our Feet

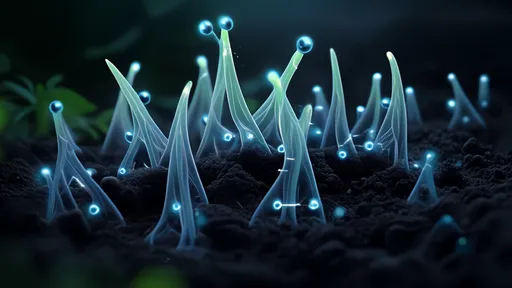

During spring growth spurts, deciduous trees flood the network with carbon to recruit fungal miners that unlock nitrogen stores. Come summer, the flow reverses as conifers facing drought stress receive emergency carbon loans from better-hydrated neighbors through fungal intermediaries. These transactions aren't random acts of kindness - the mycelium takes a percentage cut of every transaction, incentivizing efficient routing of resources to where they're needed most.

Remarkably, this underground economy exhibits features human economists would recognize. "Mother trees" - the largest, oldest individuals in a stand - function as central banks, regulating carbon flows to nurture seedlings in what scientists term "mycorrhizal facilitation." Damaged trees receive carbon subsidies from healthy neighbors through the network, a form of biological insurance policy. The system even shows speculative behavior, with fungi sometimes overextending their mineral offerings to establish relationships with promising young trees.

Climate Change and the Mycorrhizal Stock Market

Rising atmospheric CO2 levels have created a peculiar situation in these natural carbon markets. While trees photosynthesize more, they've become selective about their fungal investments. Studies show reduced carbon allocation to ectomycorrhizal partners under elevated CO2, potentially destabilizing long-evolved partnerships. The increased carbon supply appears to be inflating the "currency," changing the terms of trade between species.

Drought conditions reveal another fascinating adaptation. Trees under water stress don't simply hoard resources - they strategically redirect carbon to deep-rooted fungal connections that can access moister soil layers. This hydraulic redistribution through fungal pipelines represents a sophisticated risk management strategy, with carbon serving as both currency and collateral in underground commodity trades.

Human Implications of the Wood Wide Web

Forest management practices that disrupt these natural carbon economies may be doing more harm than previously understood. Clear-cutting doesn't just remove trees - it collapses an entire financial system that took centuries to establish. Selective harvesting that preserves mother trees and network hubs allows for faster ecosystem recovery, as the remaining infrastructure can redistribute resources to support regrowth.

The pharmaceutical industry is taking note of these discoveries as well. Many medicinal compounds originate from mycorrhizal fungi, whose chemical production appears directly tied to the carbon payments they receive from host trees. Understanding these economic relationships could revolutionize how we cultivate valuable fungal metabolites.

Perhaps most intriguingly, the mycorrhizal carbon economy suggests new approaches to climate change mitigation. Forests already operate sophisticated carbon capture and storage systems - we're just beginning to understand the rules governing their natural carbon markets. As we develop artificial carbon credit systems, we might find wisdom in how nature's original carbon currency has maintained balance for millions of years without centralized control or complex regulations.

The more we learn about these underground economies, the more we recognize that forests aren't collections of individual trees competing for resources, but interconnected communities practicing a form of resource socialism mediated by fungal bankers. In an era of climate uncertainty, understanding these natural systems of exchange and mutual aid may prove crucial for both preserving ecosystems and inspiring sustainable human systems.

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025