In the dense jungles of Central Africa, where the boundaries between human settlements and wildlife blur, a new breed of disease detectives is emerging. These "virus hunters" aren't clad in hazmat suits or wielding syringes—they're artificial intelligence systems crunching terabytes of ecological, genetic, and climatic data to predict where the next zoonotic spillover might occur. Their mission: to identify the geographical hotspots where animal-borne pathogens are most likely to jump species and trigger the next potential pandemic.

The concept isn't science fiction. Last year, an AI model developed by researchers at University College London accurately predicted three previously unknown zoonotic reservoirs in Southeast Asian bat populations by analyzing satellite imagery of deforestation patterns alongside viral genome sequences. This marked a paradigm shift—instead of reacting to outbreaks, we're now developing the capability to anticipate them.

What makes these AI systems revolutionary is their ability to process variables that human researchers might overlook. Traditional epidemiology might track known pathogens in animal populations, but the new generation of algorithms examines indirect signals: changes in land use that force wildlife into human contact, subtle mutations in animal virus strains, even fluctuations in black-market wildlife trade volumes. One particularly innovative model from the EcoHealth Alliance cross-references decades of Chinese livestock market records with climate change data to identify which species combinations pose the highest transmission risks during drought years.

The technology's potential extends beyond prediction. In Cameroon, health workers are using AI-generated risk maps to strategically position mobile vaccination units along predicted wildlife migration corridors. Meanwhile, the Pentagon's newly established Zoonotic Threat Radar program is testing whether similar algorithms can give military bases advanced warning when local animal diseases approach dangerous mutation thresholds. The line between epidemiology and national security is blurring as these systems demonstrate their capacity to foresee biological threats before they emerge.

However, the field faces significant challenges. Many high-risk regions lack the digital infrastructure to feed real-time data into predictive models. Political sensitivities around disease surveillance have led several countries to restrict access to crucial animal population datasets. Perhaps most troubling is what researchers call "the Cassandra paradox"—even accurate predictions may be ignored until an outbreak occurs, as seen when pre-pandemic warnings about coronavirus risks in Asian wet markets went unheeded.

Ethical questions loom large. Should governments act on AI predictions by culling animal populations in risk zones? How should global health priorities be balanced against local economic interests when a model flags certain agricultural practices as high-risk? The team behind the PREDICT project, which successfully identified multiple novel viruses before the COVID-19 pandemic, now advocates for international protocols governing how predictive data is used.

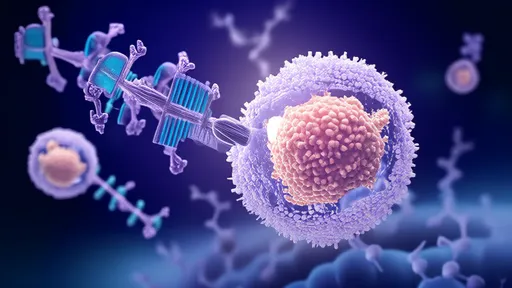

The next frontier involves moving beyond geographical predictions to forecasting specific viral mutations. DeepMind's AlphaFold team recently demonstrated that protein-structure prediction AI can model how animal viruses might evolve to infect humans. When combined with ecological data, this could enable preemptive vaccine development—creating immunizations for viruses before they exist in human populations. Such capability would fundamentally alter our relationship with pandemics, transforming them from surprises we endure to threats we neutralize in advance.

As climate change accelerates wildlife habitat loss and globalization increases human-animal contact points, these AI systems may become our most vital early warning network. The virus hunters of tomorrow won't just track diseases—they'll anticipate evolutionary pathways, model spillover scenarios, and quite possibly prevent catastrophes we can't yet imagine. In this new era of computational epidemiology, our best defense against the next pandemic might be an algorithm quietly analyzing data in some server farm, connecting dots invisible to the human eye.

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025