In a groundbreaking development that could revolutionize the treatment of vision impairment, researchers have successfully utilized hydrogel-based optical fibers to repair damaged optic nerves. This innovative approach, often referred to as "neural optical fibers," leverages the unique properties of hydrogels to create biocompatible light pathways that can restore visual signal transmission where natural nerve function has been compromised.

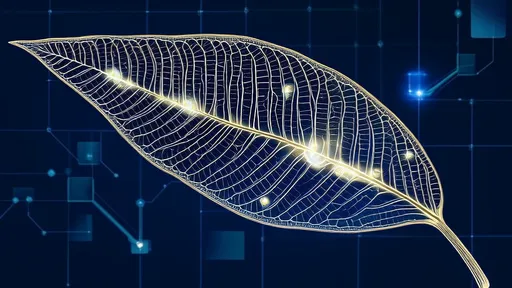

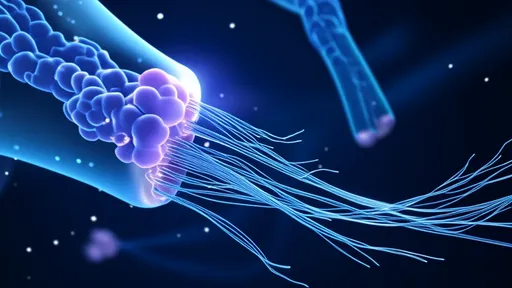

The concept draws inspiration from telecommunications fiber optics, but with a crucial biological twist. Unlike conventional glass fibers, these hydrogel channels are soft, flexible, and capable of integrating seamlessly with living neural tissue. The material's high water content mimics the natural extracellular environment, reducing inflammation and promoting cellular acceptance where synthetic materials typically fail.

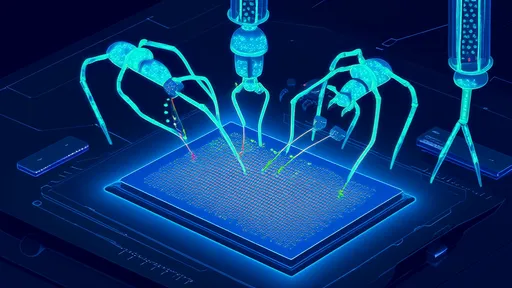

How does this neural light bridge work? The hydrogel fibers act as artificial axons, transmitting light signals across damaged sections of the optic nerve. Photoreceptor cells in the retina convert visual information into light pulses that travel through these artificial pathways, bypassing non-functioning neural segments. At the receiving end, specialized light-sensitive proteins in surviving ganglion cells decode these optical signals into electrical neural impulses that the brain can interpret.

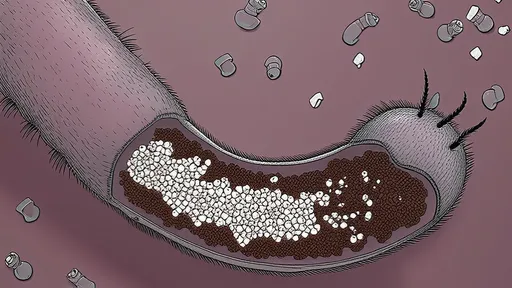

Early animal trials have shown remarkable success. In one study involving rodents with induced optic nerve damage, subjects regained approximately 60% of their light sensitivity and could track moving patterns after hydrogel fiber implantation. The treatment appears most effective when applied soon after injury, before degenerative processes completely destroy the neural architecture.

The secret lies in the hydrogel's dual functionality. Beyond mere light conduction, the material contains growth factors that encourage nerve regeneration. Over time, as natural axons begin to regrow along the hydrogel scaffold, the artificial fibers gradually degrade in a carefully timed manner. This creates a biological handoff where the regenerated nerves eventually take over the signaling function from their synthetic counterparts.

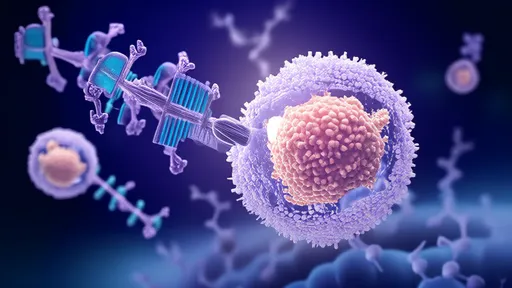

What makes this approach particularly promising is its potential to overcome the limitations of traditional neural prosthetics. Current retinal implants require external power sources and sophisticated image processing hardware. The hydrogel system, by contrast, works entirely through passive light transmission, maintaining the eye's natural optical properties while avoiding bulky electronic components.

Researchers caution that significant challenges remain before human trials can begin. The precise alignment of hydrogel fibers with both retinal cells and brain connection points presents a formidable surgical challenge. There are also questions about long-term stability and whether the regenerated nerves can maintain their connections without continued artificial support.

Nevertheless, the implications extend far beyond vision restoration. The same technology might eventually repair other neural pathways, potentially treating spinal cord injuries or neurological disorders. As one lead researcher noted, "We're not just building bridges for light - we're creating highways for neural communication that the body can eventually make its own."

The team is currently refining the hydrogel composition to improve light transmission efficiency and durability. Early versions suffered from light scattering issues, but newly developed nanocomposite formulations show dramatically improved performance. These advanced materials incorporate precisely aligned nanoparticles that guide light with minimal loss, approaching the efficiency of commercial optical fibers while maintaining perfect biocompatibility.

Ethical considerations are being carefully weighed as the technology progresses. Unlike gene therapies or stem cell treatments, the hydrogel approach represents a temporary structural intervention rather than permanent biological alteration. This transient nature may simplify regulatory approval while reducing potential long-term risks.

Funding agencies and medical foundations have taken keen interest in the project, with several increasing their investments following the publication of preliminary results. Patient advocacy groups for conditions like glaucoma and traumatic optic neuropathy are particularly enthusiastic, as these disorders currently have limited treatment options once nerve damage occurs.

Looking ahead, researchers envision a future where optic nerve repair becomes routine. The ultimate goal isn't just functional vision restoration, but the complete recreation of the eye-brain connection's natural sophistication. As the technology matures, it may offer hope to millions currently living with untreatable vision loss from nerve damage.

The convergence of materials science, photonics, and neurobiology in this project exemplifies the potential of interdisciplinary research. What began as theoretical explorations of light-matter interactions in biological contexts has blossomed into a tangible therapy that could redefine our approach to neural repair. The coming years will prove crucial as laboratory successes transition toward clinical applications.

For now, the scientific community watches with cautious optimism. Each successful animal trial brings us closer to human applications, and each material improvement increases the technology's potential efficacy. The vision of using light to heal light perception has moved from science fiction to laboratory reality - the next chapter will determine whether it can become clinical practice.

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025

By /Jul 29, 2025